During my journey through the district I visited and stayed in 6 villages, interviewing the people there and listening to their stories. According to what I have gathered so far, the logging ban had a direct effect on the lost of livelihoods in the communities I studied and it failed to protect the remaining trees and bushes from being converted to charcoal.

I was studying three types of villages and they are the ones that have had intervention from a multilateral agency, in this case through International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the ones that have had intervention from a governmental agency, in this case though the Joint Forest Management (JFM), and the ones that have had no intervention whatsoever since the ban was enforced.

IFAD has been working in some selected villages in West Khasi Hills since 1999 and the Forest Department of Meghalaya had just introduced the JFM in August 2005 in a few selected villages. It was interesting to see how the wealth-ranking index of the IFAD villages was rising since they got some support. The JFM villages have also got some support in the form of nurseries, fishponds and livestock. However, the villages that have been left out from any sort of assistance are going from bad to worst.

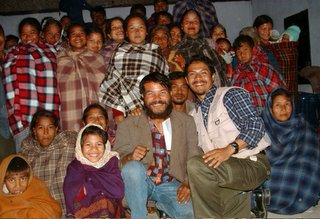

One such village that I visited called Lawsiej had 75 households and it took me about 2 hours to walk there from the closest metal road. When I reached the village I was shocked to see only 3 men who came to the meeting, which the headman had organised for me. I later found out that since there was no more livelihood opportunities in the villages, all the men had left their homes to work in coal mines 250 kms away near the Bangladesh border. They would only return home after 6 months with all sorts of respiratory diseases and later die from lack of medicines and treatment. It was very sad to see this trend of male workforce migration as a coping strategy for these poor communities in order to survive. However, before I left this village the headman gave me a rooster to take back with me as a special gift from the entire village. I was so touched by his generosity and I had to accept his gift or else I would be insulting his whole community if I had declined. Wherever I went I was treated in good faith and I realized that these people had no material belongings with them, but yet they were so happy.

One such village that I visited called Lawsiej had 75 households and it took me about 2 hours to walk there from the closest metal road. When I reached the village I was shocked to see only 3 men who came to the meeting, which the headman had organised for me. I later found out that since there was no more livelihood opportunities in the villages, all the men had left their homes to work in coal mines 250 kms away near the Bangladesh border. They would only return home after 6 months with all sorts of respiratory diseases and later die from lack of medicines and treatment. It was very sad to see this trend of male workforce migration as a coping strategy for these poor communities in order to survive. However, before I left this village the headman gave me a rooster to take back with me as a special gift from the entire village. I was so touched by his generosity and I had to accept his gift or else I would be insulting his whole community if I had declined. Wherever I went I was treated in good faith and I realized that these people had no material belongings with them, but yet they were so happy.

While I was driving to another village called Nongkrem, which had got some IFAD help, I stopped on the way to give a lift to 7 women who had just returned from the market with all their supplies. Their journey home from the market was 3 hours walk and it was already getting dark that evening. Anyway they all got into my jeep and I continued to drive in this jungle mud road where only timber carrying trucks ply on. It was therefore very difficult to navigate between the deep tracks created by the tyres of these heavy trucks. Since the ground clearance of my jeep was no high enough, I had to drive in between these deep mud tracks, which also had stones and boulders along the way. As we drove down a steep descend heavy fog suddenly appeared and both my headlights failed to dim, so I was driving blind.

In the process I managed to hit a rock on the road, which then broke the joints that held the spring of the left back tyre. The bang was loud, but I continued to drive slowly up the hill and finally after a few minutes the spring came off with the shock absorber and the left back tyre hit the mudguard of the jeep and we were stuck on the hill. Anyway to cut the story short, I had to ask all the women to disembark and walk home from there. I was lucky that there was enough space for the trucks to pass from the side of my broken jeep. After locking the jeep, I too continued on my journey on foot and reached the village in an hour just in time for my meeting.

The next morning I took a ride on one of the timber trucks to meet the people in another village called Nonglang with also got some IFAD support. In the mean time some village boys from Nongkrem walked to the market bought the spare parts for my jeep, returned to repair it and then drove the jeep back to me to Nonglang where I was still busy with my interviews. It was simply amazing as I though I would be stuck there for days. So much for jungle driving!